Lab tests are being done to see if it’s connected to other cases in the province. Thirty-two cases of measles have been confirmed in Nova Scotia so far this year – mostly in the Halifax and South Shore regions, although there were two cases recently diagnosed in Digby.

Until this year, there had been no confirmed cases of measles in Nova Scotia since 2008.

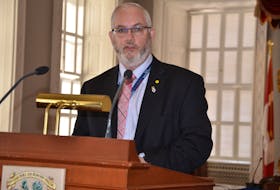

“We did have a case confirmed that was tested at Valley Regional last week,” said Dr. Trevor Arnason, medical officer of health.

He said for every confirmed case, health officials immediately try to identify who could have been exposed by identifying where the victim was at the time they would have been infectious to others.

“From that, we identify who the highest risk groups are that would require vaccination as quickly as possible,” Arnason said May 29. “So if you provide vaccination within three days of the exposure there is a good chance you can abort the infection – stop it from establishing and prevent someone from getting infected with measles.”

That means from the moment of diagnosis, health officials have to act quickly. They’re looking for immuno-compromised people, pregnant women and very young children who may have been at the same hospital – or even in the same store or gas station as the confirmed case.

“Some of those individuals can’t receive the vaccine because it’s a live virus vaccine, so we give them something called immunoglobulin, which is basically like an active form of the vaccine or the antibodies which are made from human blood from another person -- and that protects them against measles,” he explained.

The infection rate is high among unvaccinated populations, Arnason said. In fact, if a person infected with measles walked into a room of 10 unvaccinated people, nine of those people would become infected.

“There were exposures last week at the hospital, so we’ve been following up with a number of people who were at the hospital who may have been exposed in those high-risk groups – to offer them vaccine or immunoglobulin,” Arnason said.

The doctor said the Kentville patient was placed into a negative pressure room as per protocols.

Sick child

Because of privacy issues, Arnason would not confirm if the measles case at Valley Regional Hospital was the same person as detailed in a Facebook post from an Annapolis County woman on May 26.

The mother of a small child became concerned about her son’s health as far back as May 18 and said she took him to Annapolis Community Health Centre May 22 with high fever, rash and dehydration. He was isolated because it appeared he had measles but was not diagnosed because he didn’t have all the symptoms and had both of his measles vaccinations.

The child was sent home and prescribed Benadryl and Tylenol.

He was worse on May 23 and the mother took him to Valley Regional Hospital in Kentville, where she was again told it was not measles and the same treatment was again prescribed. She said they were being sent home again but she refused, demanding blood work and fluids for dehydration. When the doctor seemed hesitant, the mother said she demanded to see a pediatrician – who had the child tested for measles.

The mother described the child being unable to see as he was giving a urine sample and was rushed to ICU. The diagnosis was Kawasaki disease, an immune condition that is not contagious and not a reportable disease. The child spent the night in the hospital and was feeling better the next day, May 25, when the measles diagnosis was confirmed. Because measles is an airborne disease, the child was put in a negative pressure room until he was no longer contagious, the mother said.

It turned out he had Kawasaki disease and measles at the same time. The mother refused to take him home until tests came back normal.

On May 26, just after 2 p.m., the mother wrote:

“They just moved us back up to our room, and he's still being monitored for at least another 24 hours.”

Vaccination

Measles vaccinations work extremely well, said Arnason, noting that one vaccination is about 93 per cent effective and after two vaccinations, it is 97 per cent effective. But there’s still that three per cent chance.

How did the Kentville case contract the measles?

“That’s a good question,” said Arnason. “That’s what we’re investigating in public health now. We are currently in a measles outbreak that is centered around the western part of the province.”

He thinks the Kentville patient's condition is connected to that outbreak. Because measles is so contagious, it can at times be transmitted by casually passing somebody in a hallway or on the street, “So we haven’t identified the exact link yet and that’s what we do in our investigation.”

Sometimes it takes a little bit of time to find the link.

“For all of our 32 cases that we’ve had in the province this year, we’ve been able to identify a link eventually,” he said. “But I can’t say for sure whether we will in this case. But that’s the question top of mind for us as well is figuring out where this transmission might have occurred and how it might have occurred.”

He said if there’s another case out there that they don’t know about, the health department needs to find it and do the appropriate follow-up, get people vaccinated, and prevent it from spreading.