ANNAPOLIS VALLEY - A former paramedic has found solace in helping others as he continues his journey battling PTSD.

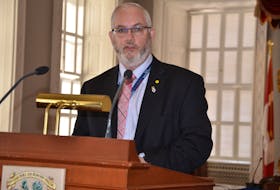

Sean Conohan launched a podcast in January 2016 as a way to learn more about post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and get people talking about a mental injury that, for far too long, has been dealt with quietly.

“When you look back, you can see the symptoms. What happens is you start to disconnect from family, you disconnect from loved ones, from friends. You may become very depressed or anxious and you just start to isolate yourself. You might not even realize it until it gets to the point where it's too much,” said Conohan.

“That's why it's so important to talk. Talk to your peers. It's so important to ask for help, which I know is scary.”

It's hard to broach the subject with employers, he adds, but, “you have to do it.”

With listeners tuning in from around the world, Conohan said he's learning and healing while he produces the monthly podcast.

The former Valley man began noticing something was amiss in 2013, but like others with PTSD, he carried on until the emotions and images were too much to bear. He said it was in January or February of 2014 that he knew he needed help.

“That's when I realized that this isn't getting any better and it's just getting worse,” said Conohan, noting it was around this time that more first responders were opening up about PTSD.

“To the back of my mind, I probably knew that was what was happening to me. But of course, like everybody else, I didn't want to admit it and just wanted to think that I'm tough enough, that I'll just get through it and it'll get better and of course, that doesn't work,” said Conohan.

In March 2014, he found himself without a job, income or benefits.

“And for me, personally, without an identity. For 17 years, I identified myself as a paramedic. I had lost all of those things,” said Conohan.

Getting help

As life began to spiral, Conohan found a clinical psychologist, Dr. Robin McGee, of Port Williams, and the pair clicked. The Tema Conter Memorial Trust submitted a cheque for $1,000 to help with his treatment, and Conohan said that was when his life began to turn around.

“Without that, I know I probably wouldn't be here today. I probably would be a statistic,” said Conohan, referring to the number of first responders who die by suicide annually.

“That's why I'm always excited, honoured and feel blessed to be able to work with Tema Conter Memorial Trust because they saved my life. I owe them my life.”

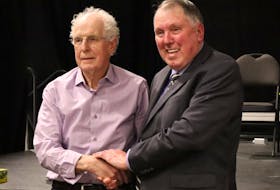

Conohan was honoured earlier this month when he received the 2017 Tema Media Award for his work on UpTalk.

Vince Savoia, the founder and executive director of Tema Conter Memorial Trust – Canada's leading provider of peer support, family assistance, education and training for first responders - said presenting the award to Conohan was a 'no-brainer.'

“As you can appreciate, first responders — as part of their job — attend to individuals who are struggling with mental health issues. So, to the first responder, it's almost an embarrassment to be diagnosed with any sort of mental health injury or illness,” Savoia said.

“In Canada, as a whole, there is still a very strong stigma around mental health and mental illness. What the podcast basically does for the first responder community is it chips away at that stigma. It allows individuals who have experienced either a mental health injury or who are struggling with addictions and/or mental health illness to come forward and share their story with their colleagues. To those who are listening to the podcast, it truly is a sense of not being alone.”

Savoia said Conohan has been a positive influence in helping to shine a light on the subject.

Savoia, who was a paramedic and emergency medical dispatcher, said Canada's current health care system does not provide enough mental health resources for first responders, which is why the organization started helping fund treatment.

“We don't have enough mental health resources in place to get to these people soon enough. For example, in Canada, we have roughly about 4,700 psychiatrists to serve a population of about 35 million people. It's not unheard of if you're referred to a psychiatrist, your wait time can be anywhere from six months to two years,” he said.

Those who visit a privately practicing psychologist or social worker will be paying out of pocket for treatment, he said.

“If we access those services outside of a hospital setting, we now have to pay for those services out of pocket,” said Savoia, noting it usually costs between $150 to $250 per hour.

Tema's Peer Support and Family Assistance Fund launched in 2015 in partnership with Wounded Warriors Canada. More than $260,000 has been put toward funding mental health care for more than 200 first responders and their families. The organization funds up to $1,000 in order to help first responders get the counselling they need.

“We know through research that if we can get someone to see a psychologist sooner — or directly after a critical event or critical incident type call — their therapy sessions generally would be between six to 10 sessions. If we prolong that referral and a first responder goes years without seeing a psychologist, chances are their treatment may take years,” he said. “It's part of our proactive approach to mental health.”

The funding is sent directly to the psychologist. They've helped about 20 people from the east coast since the fund was created.

Read more stories in this series:

• Falmouth psychologist launching new treatment facility, comic book series to help tackle PTSD

• Pension for Life for Veterans will help military personnel with PTSD: federal minister

Finding strength to move on

Conohan, who grew up in New Minas, moved to Windsor and commuted to his job as a paramedic in Halifax. He lived in the area for 10 years before moving to Bedford.

Prior to launching his first podcast in 2016, Conohan joined the Brooklyn Fire Department. He began realizing that he was experiencing the same symptoms he had near the end of his paramedic career.

“It's hard to be a first responder for years and then, all of a sudden, not be able to do it. You fight it, you try to push through it,” said Conohan, who first signed up to be a firefighter in 1993 with the New Minas Volunteer Fire Department.

But after speaking with a deputy chief in Brooklyn, Conohan realized he needed to refocus his attention on his own well-being and leave the BFD behind.

“So I had to let it go, and I had to be OK with that, which didn't come easily, but I know it's just not something I can do,” he said.

“Now what I can do is try to help them, try to help everybody as much as I can by bringing on as many interesting people as I can that can teach us things.”

His UpTalk podcast has 20 episodes featuring 35 guests. Under new branding with Tema Conter Memorial Trust, the podcast will carry on with Conohan at the helm.

He says he's humbled by the support he's received, by the experts and guests who participate in the podcast, and by the feedback he receives from listeners.

Conohan said first responders need to find ways to process the calls they attend; otherwise, they will start to take a toll.

“If you don't take care of each traumatic event as it happens, if you're not careful, they start to pile up. You may be able to go 25 years into a career and it's never an issue. Or, you may only get five years in,” said Conohan.

The former paramedic likes to draw an analogy between the brain and closet space.

“Everybody's space is different. I always say it's like a closet, but everybody's closet is a different size,” he said. “When your closet gets full and it overflows and you get buried with it, that's when everything falls apart.”

Treatment is also individualized. Some patients respond best to eye movement desensitization reprocessing therapy, while others prefer cognitive processing therapy or exposure therapy.

“The important thing to remember is that not everybody is the same so the same therapy or the same psychologist isn't going to work for everybody.”

Conohan says he believes PTSD can be cured, but there will be residual effects that last a lifetime.

“For me, PTSD is the misfiled memories that for some reason, your brain just didn't process correctly. I think you can fix that through whatever therapy works for you,” he said.

“But now, the other side of that is PTSD comes with a lot of moral injuries. What I deal with every day is feelings of guilt, feelings of bitterness over what happened – why me? It could be depression, it could be anxiety.”

Conohan said it's up to each person to make changes to their personal habits in order to mitigate those symptoms.

“Everybody says 'I won't be the same person that I am.' Well, no, you won't be. You'll be better; you'll be stronger. You'll know how to get through the tough times. You'll have tools that you can use when things are tough,” he said.

Conohan said as long as there are first responders that die by suicide, his work won't be done.

“In 2017, we still had 56 first responder reported suicides. So far in 2018, we have two. As long as that's still happening, that's a message that our work is not done and we need to keep going,” he said.

What is PTSD?

According to Statistics Canada, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) “can occur after witnessing or experiencing a traumatic event involving actual or threatened death, serious injury or violent personal assault, such as sexual assault. The response to the event is marked by extreme fear and helplessness. Symptoms must persist for a minimum of one month and could include: repeated reliving of the event, disturbance of day-to-day activity, avoidance of stimuli associated with the event, and irritability, outbursts of anger, or sleeping difficulty.”

Go online: Learn more about TEMA at www.tema.ca; and the podcast can be found at: https://soundcloud.com/user-603973533