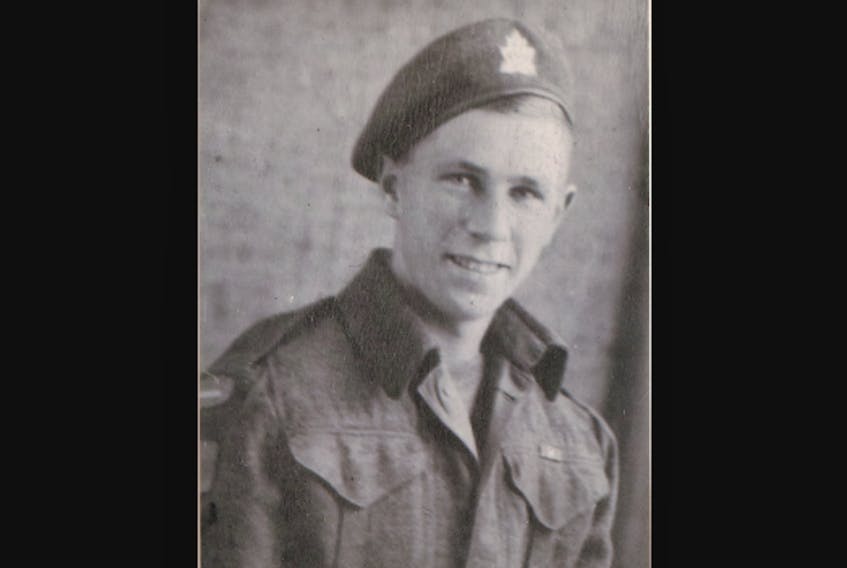

MELANSON, N.S. — In the Second World War, late in 1944, Kings County native Pte. Glen Allen, an infantryman with the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry was missing during the battle to liberate Holland. Allen’s fate wouldn’t be known for months. Was he wounded and stranded somewhere on the battlefield, a fatality, a prisoner of war? The Canadian military couldn’t provide answers, but a lady did, a Scottish lady who lived more than 2,000 miles away from Allen’s home and far from the battlefield. This is Pte. Allen’s wartime story, a story about good arising from Nazi wartime propaganda, and a tale about an amazing connection across the waters.

Midway through 1944, the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry (RHLI) fought their way through Normandy as part of 2nd Canadian Division’s assault on France. In their ranks was a young private from Melanson. He had enlisted in Halifax and after basic training in New Glasgow was posted out of the province to the RHLI, a common practice when regiments were undermanned.

Glen Lorraine Allen (1923-1999) was 21 when his regiment landed in France just after D-Day. The RHLI participated in the Battle of Normandy, was with Allied forces in the fight to capture the port of Antwerp and in the effort to liberate Holland.

In a way, Allen might have been considered a hard-luck soldier. On Sept. 5, 1944, Ottawa informed the Allen family that he had been wounded in action on Aug. 29, the extent of his injuries unknown. Ten days later another telegram from Ottawa stated that Allen had been shot in the neck, a non-life-threatening wound but one that would trouble him for the rest of his days. Allen was wounded again on Oct. 17, with Ottawa informing his family that the extent of this wound was unknown.

Then came the struggle to liberate Holland and Allen, apparently recovered from his wounds, was with his regiment and again in the thick of the fighting. During the winter of 1944-45, Allen’s battalion participated in the Battle of the Scheld on the border between Belgium and Holland. Here, in five weeks of difficult fighting, the Canadian Army suffered over 6,000 casualties.

Some of the fiercest fighting involving the RHLI took place in the Dutch village of Woensdrecht. RHLI war records indicate they literally had to fight from house to house to take the village. It was here that Allen became one of the most dreaded casualties of the war, an MIA. Allen simply disappeared from the battlefield and the next day he was marked in casualty lists as missing in action. His fate was unknown. Was he a fatality? Had he been wounded and unable to find his back to the Canadian lines? Had he been taken as a prisoner of war? It would be three months before these questions were answered and it wasn’t Ottawa who let Allen’s family know of his fate. In the end, the answers to these questions came from faraway Scotland.

It is about 2,600 miles from Kings County to Galston, a community of 5,000 on the Irvine River in Scotland. Here and elsewhere in Great Britain, it was common to listen to nightly propaganda broadcasts from Germany. The sole purpose of these broadcasts, Germany Calling, was to weaken pro-British sentiment. While known as propaganda, they often offered clues to the fate of Allied troops and air crews and were monitored closely by the military and by civilians alike. One of the ploys used on the broadcasts was to have captured soldiers and airmen send messages to their families. Galson resident Jessie Craig was listening to the broadcasts on an October evening in 1944 when a Nova Scotia soldier, Glen L. Allen, sent a message to his mother. On hearing this, Craig took pen in hand and wrote the following letter:

“Dear Mrs. Allen:

“Have you had any news of your son, Glen, lately? Although I am a stranger, I am in a position to give you a message from your son. You see while listening to the radio tonight I heard messages being read that had come from soldiers who had been taken prisoner. I was able to hear the message that came from your son, Pte. G. L. Allen F56871, and the announcer asked if anyone hearing the messages would let prisoner’s folks know. I was only too pleased to forward the information.

“Glen wants you to know that he is a (prisoner of war) in Germany. He is, however, being treated well and says he will write as soon as he can. He sends all his love.

“Well, Mrs. Allen, that is what I had to let you know. But have good cheer, for who knows, Glen may be home again with you. God bless you Mrs. Allen and Glen too.”

Craig’s letter solved the mystery about what happened to Glen Allen in Woensdrecth. Eventually, two letters arrived that Glen wrote from the prison camp, confirming he was alive and being treated well. The broadcast Jessie Craig heard brought another letter from Ottawa stating in effect that “these short wave broadcasts from Germany form part of enemy propaganda and are treated as such …. but usually when a name is heard from Germany it is eventually officially confirmed.”

Glen Allen survived the German prison camp and was freed when it was liberated by the British Army on April 21, 1945. He returned home after being officially discharged on Aug. 2, 1945. He settled in New Minas and, in following years, a Department of Veteran Affairs course in woodworking led to a position at Horton High School, where he taught Industrial Arts for 20 years.

Reminiscing about his war service, his son Malcolm remembers that to his dying day his father couldn’t eat cabbage, thanks to having been fed so much of it in prison camp. “But he never forgot his war years and never missed the reunions,” Malcolm says. “He was especially proud to be a recipient of the Liberation of Holland medal. He was honored to be one of thousands of Canadian veterans invited to the Netherlands when the country celebrated the anniversary of its liberation.”

Letter writer Jessie Craig was never in contact with Allen or his family after the war, and he always wondered how she found his home address. All these years later, it remains a mystery.

RELATED STORIES:

VIDEO: South Nictaux veteran recounts risky Second World War missions

Greenwood veteran recalls the dangers of serving in Second World War

Second World War veteran recounts horrors of Battle of Hong Kong